The Untold Story of California’s Farmworker Movement: Beyond the Grape Boycott

In the sun-drenched fields of California, a movement was born that would forever change the landscape of agricultural labor rights in America. As we delve into the rich history of the farmworker movement, we uncover stories of struggle, solidarity, and triumph that extend far beyond the iconic grape boycott. Join us as we explore the complex tapestry of California’s farmworker activism, from its humble beginnings to its lasting impact on labor relations today.

“The 1965-1970 grape boycott movement resulted in a 17% increase in wages for California farmworkers.”

The Roots of Resistance: Early Farmworker Organizing

The story of California’s farmworker movement didn’t begin with Cesar Chavez, though he would become its most recognized face. The seeds of resistance were sown decades earlier, as migrant workers faced harsh conditions, meager wages, and little legal protection. In the early 20th century, Filipino and Mexican laborers began to organize, laying the groundwork for what would become a powerful coalition.

In 1962, the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA) was founded, marking a crucial step in organized labor for agricultural workers. This organization, later renamed the United Farm Workers (UFW), would become the driving force behind many of the movement’s most significant achievements.

The Delano Grape Strike: A Turning Point

The year 1965 marked a watershed moment in the farmworker movement with the beginning of the Delano Grape Strike. While Cesar Chavez is often credited as the sole leader of this action, the truth is more complex and inclusive.

“Filipino labor leaders initiated the Delano grape strike in 1965, eight days before the more widely recognized Mexican-American involvement.”

On September 8, 1965, Filipino farmworkers, led by Larry Itliong and the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC), walked off the job in Delano, California. This brave act set the stage for what would become a five-year struggle that captured national attention and sparked a wave of consumer activism.

Eight days later, on September 16, Cesar Chavez and the NFWA joined the strike, recognizing the power of unity between Filipino and Mexican workers. This coalition formed the backbone of the United Farm Workers Organizing Committee, which later became the UFW.

Nonviolent Resistance and the Power of the Boycott

The Delano Grape Strike introduced innovative tactics that would define the farmworker movement. Inspired by the principles of Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr., Chavez and his fellow organizers emphasized nonviolent resistance as a key strategy.

One of the most effective tools in their arsenal was the grape boycott. By appealing to consumers nationwide to stop buying grapes, the movement exerted economic pressure on growers. This tactic not only brought attention to the plight of farmworkers but also created a sense of solidarity between urban consumers and rural laborers.

The boycott’s success was unprecedented. It resulted in a significant increase in wages and improved working conditions for farmworkers. More importantly, it demonstrated the power of consumer activism and nonviolent resistance in achieving social change.

Beyond Chavez: Recognizing the Diversity of Leadership

While Cesar Chavez remains the most recognized figure of the farmworker movement, it’s crucial to acknowledge the contributions of other leaders, particularly those from the Filipino community.

Larry Itliong, a seasoned labor organizer, played a pivotal role in initiating the Delano Grape Strike. His experience and leadership were instrumental in building the multiethnic coalition that gave the movement its strength.

Johnny Itliong, Larry’s son, has been working to ensure his father’s contributions are not forgotten. He emphasizes the importance of recognizing the diverse voices that shaped the movement:

“My father was the one who started the Delano Grape Strike. The Delano Grape Strike was huge in this movement,” Johnny Itliong stated in an interview with Imperial Valley Press.

This perspective highlights the need for a more inclusive narrative of the farmworker movement, one that acknowledges the contributions of all its participants.

The Legacy of Unity: The Power of Solidarity

One of the most powerful symbols of the farmworker movement is the Unity Clap, a rhythmic clapping sequence used to rally workers during meetings and protests. Interestingly, this tradition has roots in the Philippines, where it was developed as a way to overcome language barriers among workers.

Johnny Itliong explains:

“It was from the strikes in the Philippines. In the Philippines, there’s over 1,000 different languages, thousands of dialects, right? So the only way to get everybody to rally together that didn’t understand other languages was to what? And it’s a great way to start things and a great way to end things.”

This tradition exemplifies the power of solidarity and the importance of finding common ground in the face of diversity – a lesson that remains relevant in today’s labor movements.

Legislative Victories and Ongoing Challenges

The farmworker movement’s efforts led to significant legislative victories. In 1975, California passed the Agricultural Labor Relations Act, granting farmworkers the right to form unions and engage in collective bargaining. This landmark legislation was a direct result of the pressure exerted by the movement.

However, the struggle for farmworkers’ rights is far from over. Many of the challenges faced by agricultural laborers in the 1960s persist today. Issues such as fair wages, safe working conditions, and access to healthcare remain at the forefront of modern farmworker advocacy.

The Movement Today: Continuing the Fight for Justice

The spirit of the farmworker movement lives on in contemporary labor organizing and community activism. Across California and beyond, farmworkers and their allies continue to advocate for improved conditions and fair treatment.

In Brawley, California, community members recently gathered for a march honoring Cesar Chavez Day. This event not only celebrated past achievements but also highlighted ongoing challenges in the agricultural industry.

Dr. Miguel Chavez, a professor of Chicano studies at Imperial Valley College, emphasized the importance of engaging younger generations in this ongoing struggle:

“It is a great honor to see so much youth here. I’m really excited and proud of my students who brought their families and children to this gathering because I firmly believe that we need to start them young.”

This sentiment underscores the enduring relevance of the farmworker movement and the need to pass its lessons on to future generations.

The Role of Technology in Modern Agricultural Labor

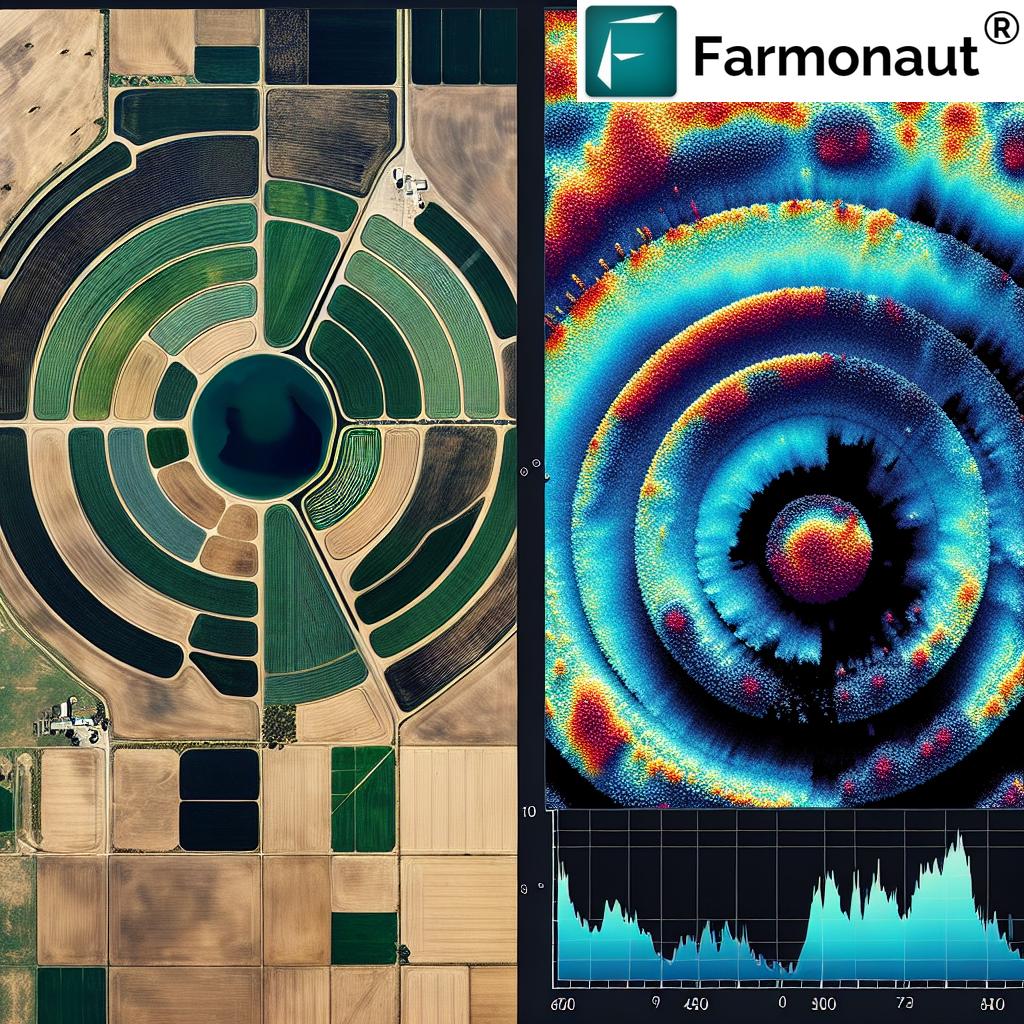

As we consider the future of agricultural labor and farmworkers’ rights, it’s important to recognize the role that technology can play in addressing some of the industry’s longstanding challenges. Modern agricultural technology solutions, such as those offered by Farmonaut, have the potential to improve working conditions and increase efficiency in ways that benefit both farmers and farmworkers.

Farmonaut’s crop plantation and forest advisory services utilize satellite imagery and AI to provide valuable insights into crop health and optimal resource management. By helping farmers make more informed decisions about irrigation, fertilizer use, and pest control, these tools can potentially reduce the physical strain on farmworkers while improving overall productivity.

Additionally, Farmonaut’s carbon footprinting feature allows agricultural businesses to monitor and reduce their environmental impact. This aligns with the growing emphasis on sustainable farming practices, which can lead to healthier working environments for farmworkers.

While technology alone cannot solve all the challenges faced by farmworkers, innovations like these represent a step towards more sustainable and equitable agricultural practices.

Preserving the Legacy: Education and Commemoration

Efforts to preserve and honor the legacy of the farmworker movement are ongoing. Cesar Chavez Day, observed on March 31, is now recognized as a federal commemorative holiday in the United States. While it’s not a full federal holiday (government offices remain open), many states, including California and Arizona, mark the occasion with educational events, service projects, and marches.

These commemorations serve as important reminders of the movement’s achievements and the work that still needs to be done. They also provide opportunities for community engagement and education, ensuring that the lessons of the past continue to inform present-day struggles for justice.

The Global Context: Farmworkers’ Rights Around the World

While our focus has been on California’s farmworker movement, it’s important to recognize that the struggle for agricultural workers’ rights is a global issue. From the vineyards of France to the tea plantations of India, farmworkers around the world face similar challenges of low wages, harsh working conditions, and limited legal protections.

The strategies and tactics developed by California’s farmworker movement – nonviolent resistance, consumer boycotts, and coalition-building – have inspired labor organizers worldwide. At the same time, the movement continues to draw inspiration from global struggles for workers’ rights and social justice.

Conclusion: The Ongoing Struggle for Dignity and Justice

As we reflect on the rich history of California’s farmworker movement, we’re reminded that the struggle for justice is ongoing. The achievements of leaders like Cesar Chavez, Larry Itliong, and countless unnamed activists have improved the lives of many agricultural workers, but significant challenges remain.

Today’s farmworker advocates continue to fight for fair wages, safe working conditions, and dignified treatment. They face new challenges, from climate change impacts on agriculture to the complexities of immigration policy. Yet they also have new tools at their disposal, from social media organizing to innovative agricultural technologies.

The story of California’s farmworker movement is far from over. It’s a living legacy, continually shaped by those who carry forward the torch of justice. As we honor this history, we’re called to consider our own role in supporting fair labor practices and sustainable agriculture.

Whether through consumer choices, political advocacy, or community engagement, each of us has the power to contribute to a more just and equitable food system. The farmworker movement reminds us that change is possible when we stand together in solidarity, across cultural divides and generations, united in the pursuit of dignity and justice for all.

FAQ: California’s Farmworker Movement

- Who started the Delano Grape Strike?

The Delano Grape Strike was initiated by Filipino farmworkers led by Larry Itliong and the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC) on September 8, 1965. Cesar Chavez and the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA) joined the strike eight days later. - What was the significance of the grape boycott?

The grape boycott was a powerful tool that brought national attention to farmworkers’ struggles, exerted economic pressure on growers, and resulted in improved wages and working conditions for agricultural laborers. - How did the farmworker movement impact legislation?

The movement’s efforts led to the passage of the California Agricultural Labor Relations Act in 1975, which granted farmworkers the right to form unions and engage in collective bargaining. - What is the Unity Clap?

The Unity Clap is a rhythmic clapping sequence used in farmworker rallies and meetings. It originated in the Philippines as a way to overcome language barriers and build solidarity among workers. - How is Cesar Chavez Day observed?

Cesar Chavez Day, observed on March 31, is a federal commemorative holiday in the U.S. Many states mark the occasion with educational events, service projects, and marches to honor Chavez’s legacy and the broader farmworker movement.

Earn With Farmonaut: Earn 20% recurring commission with Farmonaut’s affiliate program by sharing your promo code and helping farmers save 10%. Onboard 10 Elite farmers monthly to earn a minimum of $148,000 annually—start now and grow your income!

Thank you for this insightful article!